Mailing a letter is about to get a little more expensive.

Regulators

on Tuesday approved a temporary price hike of 3 cents for a first-class

stamp, bringing the charge to 49 cents a letter in an effort to help

the Postal Service recover from severe mail decreases brought on after

the 2008 economic downturn.

Many consumers won’t feel the price increase

immediately. Forever stamps, good for first-class postage whatever the

rate, can be purchased at the lower price until the new rate is

effective Jan. 26.

The higher rate will last no more than two years, allowing the Postal

Service to recoup $2.8 billion in losses. By a 2-1 vote, the

independent Postal Regulatory Commission rejected a request to make the

price hike permanent. (PK'S NOTE: Riiiiight)

The higher cost “will last just long enough to recover the loss,” Commission Chairman Ruth Y. Goldway said.

Bulk mail, periodicals and package service rates rise 6 percent, which

is likely to draw significant consternation from the mail industry.

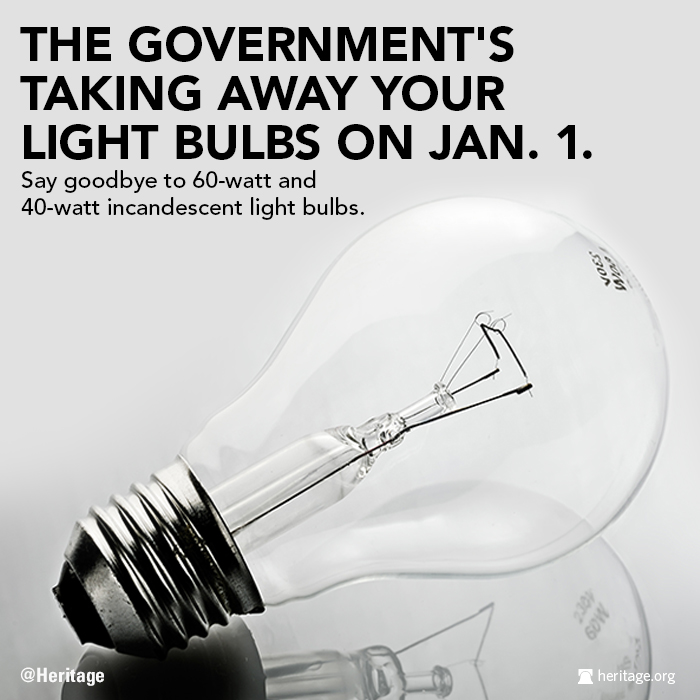

If your New Year’s resolution is to change your light bulbs, don’t worry—the federal government’s here to help.

Beginning January 1, 2014, the federal government will ban the use of 60-watt and 40-watt incandescent light bulbs.

The light bulb has become a symbol in the fight for consumer freedom

and against unnecessary governmental interference into the lives of the

American people.

In 2007, Congress passed and President George W. Bush signed into law

an energy bill that placed stringent efficiency requirements on

ordinary incandescent bulbs in an attempt to have them completely

eliminated by 2014. The law phased out 100-watt and 75-watt incandescent

bulbs last year.

Proponents of government-imposed efficiency standards and regulations

will say, “So what? There are still plenty of lighting options on the

shelves at Home Depot; we’re saving families money; and we’re reducing

harmful climate change emissions.”

The “so what” is that the federal government is taking decisions out of the hands of families and businesses, destroying jobs,

and restricting consumer choice in the market. We all have a wide

variety of preferences regarding light bulbs. It is not the role of the

federal government to override those preferences with what it believes

is in our best interest.

Families understand how energy costs impact their lives and make decisions accordingly. Energy efficiency has improved dramatically over the past six decades—long before any national energy efficiency mandates.

If families and firms are not buying the most energy-efficient

appliance or technology, it is not that they are acting irrationally;

they simply have budget constraints or other preferences such as

comfort, convenience, and product quality. A family may know that buying

an energy-efficient product will save them money in the long term, but

they have to prioritize their short-term expenses. Those families

operating from paycheck to paycheck may want to opt for a cheaper light

bulb and more food instead of a more expensive light bulb and less food.

Some may read this and think: Chill out—it’s just a light bulb. But it’s not just a light bulb. Take a look at the Department of Energy’s Federal Energy Management Program. Basically anything that uses electricity or water in your home or business is subject to an efficiency regulation.

When the market drives energy efficiency, it saves consumers money.

The more the federal government takes away decisions that are better

left to businesses and families, the worse off we’re going to be.

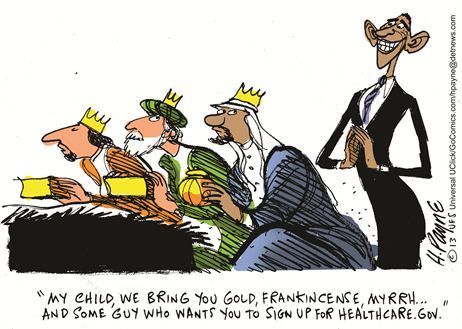

Health insurance should be individual, portable across jobs, states and providers, and lifelong and renewable.

.By John H Cochrane

.....The U.S. health-care market is

dysfunctional. Obscure prices and $500 Band-Aids are legendary. The

reason is simple: Health care and health insurance are strongly

protected from competition. There are explicit barriers to entry, for

example the laws in many states that require a "certificate of need"

before one can build a new hospital. Regulatory compliance costs,

approvals, nonprofit status, restrictions on foreign doctors and nurses,

limits on medical residencies, and many more barriers keep prices up

and competitors out. Hospitals whose main clients are uncompetitive

insurers and the government cannot innovate and provide efficient cash

service.

We need to permit the

Southwest Airlines,

LUV -0.48%

Wal-Mart,

WMT +0.35%

Amazon.com

AMZN +0.41%

and Apples of the world to bring to health care the same dramatic

improvements in price, quality, variety, technology and efficiency that

they brought to air travel, retail and electronics. We'll know we are

there when prices are on hospital websites, cash customers get

discounts, and new hospitals and insurers swamp your inbox with

attractive offers and great service.

The

Affordable Care Act bets instead that more regulation, price controls,

effectiveness panels, and "accountable care" organizations will force

efficiency, innovation, quality and service from the top down. Has this

ever worked? Did we get smartphones by government pressure on the 1960s

AT&T

T +0.04%

phone monopoly? Did effectiveness panels force United Airlines

and American Airlines to cut costs, and push TWA and Pan Am out of

business? Did the post office invent

FedEx,

FDX +0.68%

UPS and email? How about public schools or the last 20 or more health-care "cost control" ideas?

Only

deregulation can unleash competition. And only disruptive competition,

where new businesses drive out old ones, will bring efficiency, lower

costs and innovation.

Health insurance

should be individual, portable across jobs, states and providers;

lifelong and guaranteed-renewable, meaning you have the right to

continue with no unexpected increase in premiums if you get sick.

Insurance should protect wealth against large, unforeseen, necessary

expenses, rather than be a wildly inefficient payment plan for routine

expenses.

People want to buy this

insurance, and companies want to sell it. It would be far cheaper, and

would solve the pre-existing conditions problem. We do not have such

health insurance only because it was regulated out of existence.

Businesses cannot establish or contribute to portable individual

policies, or employees would have to pay taxes. So businesses only offer

group plans. Knowing they will abandon individual insurance when they

get a job, and without cross-state portability, there is little reason

for young people to invest in lifelong, portable health insurance.

Mandated coverage, pressure against full risk rating, and a

dysfunctional cash market did the rest.

Rather

than a mandate for employer-based groups, we should transition to fully

individual-based health insurance. Allow national individual insurance

offered and sold to anyone, anywhere, without the tangled mess of state

mandates and regulations. Allow employers to contribute to individual

insurance at least on an even basis with group plans. Current group

plans can convert to individual plans, at once or as people leave. Since

all members in a group convert, there is no adverse selection of sicker

people.

ObamaCare

defenders say we must suffer the dysfunction and patch the law, because

there is no alternative. They are wrong. On Nov. 2, for example,

New York Times

NYT +0.96%

columnist

Nicholas Kristof

wrote movingly about his friend who lost employer-based insurance

and died of colon cancer. Mr. Kristof concluded, "This is why we need

Obamacare." No, this is why we need individual, portable,

guaranteed-renewable, inexpensive, catastrophic-coverage insurance.

On Nov. 15, MIT's

Jonathan Gruber,

an ObamaCare

architect, argued on Realclearpolitics that "we currently have a highly

discriminatory system where if you're sick, if you've been sick or

you're going to get sick, you cannot get health insurance." We do. He

concluded that the Affordable Care Act is "the only way to end that

discriminatory system." It is not.

On

Dec. 3, President

Obama

himself said that "the only alternative that Obamacare's critics

have, is, well, let's just go back to the status quo." Not so.

What

about the homeless guy who has a heart attack? Yes, there must be

private and government-provided charity care for the very poor. What if

people don't get enough checkups? Send them vouchers. To solve these

problems we do not need a federal takeover of health care and insurance

for you, me, and every American.

No other country has a free health market, you may object. The rest of the world is closer to single payer, and spends less.

Sure.

We can have a single government-run airline too. We can ban FedEx and

UPS, and have a single-payer post office. We can have government-run

telephones and TV. Thirty years ago every other country had all of

these, and worthies said that markets couldn't work for travel, package

delivery, the "natural monopoly" of telephones and TV. Until we tried

it. That the rest of the world spends less just shows how dysfunctional

our current system is, not how a free market would work.

While

economically straightforward, liberalization is always politically

hard. Innovation and cost reduction require new businesses to displace

familiar, well-connected incumbents. Protected businesses spawn "good

jobs" for protected workers, dues for their unions, easy lives for their

managers, political support for their regulators and politicians, and

cushy jobs for health-policy wonks. Protection from competition allows

private insurance to cross-subsidize Medicare, Medicaid, and emergency

rooms.

But it can happen. The first step is, the American public must understand that there is an alternative. Stand up and demand it.

Why All Children Should Learn to Work

Jack Kingston’s “no free lunch” suggestion doesn’t go far enough

By Jillian Kay Melchior

Georgia Representative Jack Kingston came

under fire last week for suggesting that schoolchildren who receive free

lunches “pay a dime, pay a nickel . . . or maybe sweep the floor of the

cafeteria,” an effort he suggested would help get “the myth out of

their head that there is such a thing as a free lunch.” The proposal has

immediately drawn comparisons to Newt Gingrich’s suggestion in 2011

that poor schools fire union janitors and instead hire needy kids who

want to earn an extra buck.

The uproar has been swift and

emotional, with critics claiming that Kingston, like Gingrich before

him, is a mean old bully, exacerbating the already awful lives of poor

kids.

“Have you ever seen what children are like?” wrote Jim Newell at Salon. “God,

they’re awful. The well-off ones would dump their whole lunch trays on

the floor and say to the poor kid, ‘Hey, Rags, clean ’er up, because ha

ha ha, your parents have a low income.’ Not only would you be scarring

poor kids for life; you’d also give a whole new generation of non-poor

kids ample practice time to develop into [a**holes].” Josh Israel at ThinkProgress

complained that Kingston’s proposal would incite truly needy children

to turn down the lunch being offered to them, for fear of being singled

out. And The Root’s Keli Goff wrote that Kingston should do

“something substantive to help these children break the cycle of poverty

so they don’t have to listen to you threatening to use their kids for

slave labor a generation from now.”

But the real problem with

Kingston’s proposal is that it doesn’t go far enough. Children —

regardless of whether or not they receive a free or reduced lunch —

would benefit from chipping in with school cleaning. Moreover, society

would benefit.

I know that from my own experience. I spent most of my elementary years

at Noah Webster Christian School in Cheyenne, Wyo. A tiny school, it

operated out of churches on a shoestring budget. Dads chipped in one

summer and built a playground for us. The education was excellent, but a

janitorial staff was far beyond reach, so we children were expected to

pitch in.

In true Mary Poppins spirit, teachers often made a

game of it: Shaving cream removes ink smudges from desks mid-semester,

and for some reason, it’s much more fun to speed-scribble multiplication

tables in the mousse-y mess than it is to write them in a notebook. But

fun wasn’t guaranteed, and chores came as regularly as homework. On

Fridays, children vacuumed and wiped down the chalkboards. And on one of

the last days of each semester, we spent the day deep-cleaning —

trotting around with plastic buckets, scrubbing floor trim and washing

the white-brick walls of the hallway.

As much as I complained at

the time, that responsibility taught us to value public property. It

also gave us a stake in our school. We worked hard to keep it clean and

functioning, and that taught us to appreciate the resources we had. The

experience also gave us practical competencies far beyond what home-ec

classes offer. Finally, it was strangely empowering: We were trusted

to mix Pine-Sol with water (albeit with supervision), and our teachers

understood that just because we weren’t yet twelve didn’t mean we were

idiots incapable of climbing a ladder to dust without falling to our

untimely demise.

The values of class-chore time were lost on me,

of course — until I transferred to public school in fifth grade.

Children made messes with reckless abandon. It didn’t matter if you left

a trail of crumbs behind you in the cafeteria or if you tracked in mud

from recess; you wouldn’t be the one cleaning it up. In contrast, in

third grade at Noah, I once spent a recess scrubbing out my desk after

I’d forgotten an apple in it over break. It had molded and liquefied,

and it smelled terrible. It was my fault, and because it was my problem

to deal with, I was more responsible in the future.

But that ethic runs contrary to the progressive mindset, which infantilizes adults — and children, much more so. The Root’s

Goff continued her critique of Kingston’s proposal by suggesting more

handouts for poor kids, including “comprehensive sexual education,

low-cost contraception and loan-free financial college aid so these kids

can have a real chance to compete.” And then she let slip the

underlying theory:

The words “personal responsibility”

should almost always be limited to adults, and to those teens nearing

adulthood who have the capacity to make informed decisions, good and

bad, and to be held accountable for them accordingly.

That’s

a radical perspective. Education has, historically, been a moral

endeavor as much as a practical one. Not only does it equip our young to

someday gainfully provide for themselves and their families; it also

prepares children to gradually assume responsibility. Good education

leads to self-government, and the education that separates learning from

responsibility does children no favors. So by all means, pass the mop

to all children, rich or poor.