Any one whose labors take him into the far

reaches of the country, as ours lately have done, is bound to mark how

the years have made the land grow fruitful.

This

is indeed a big country, a rich country, in a way no array of figures

can measure and so in a way past belief of those who have not seen it.

Even those who journey through its Northeastern complex, into the

Southern lands, across the central plains and to its Western slopes can

only glimpse a measure of the bounty of America.

And a traveler cannot but be struck

on his journey by the thought that this country, one day, can be even

greater. America, though many know it not, is one of the great

underdeveloped countries of the world; what it reaches for exceeds by

far what it has grasped.

So the visitor

returns thankful for much of what he has seen, and, in spite of

everything, an optimist about what his country might be. Yet the

visitor, if he is to make an honest report, must also note the air of

unease that hangs everywhere.

For the

traveler, as travelers have been always, is as much questioned as

questioning. And for all the abundance he sees, he finds the questions

put to him ask where men may repair for succor from the troubles that

beset them.

His countrymen cannot forget

the savage face of war. Too often they have been asked to fight in

strange and distant places, for no clear purpose they could see and for

no accomplishment they can measure. Their spirits are not quieted by the

thought that the good and pleasant bounty that surrounds them can be

destroyed in an instant by a single bomb. Yet they find no escape, for

their survival and comfort now depend on unpredictable strangers in

far-off corners of the globe.

How can

they turn from melancholy when at home they see young arrayed against

old, black against white, neighbor against neighbor, so that they stand

in peril of social discord. Or not despair when they see that the cities

and countryside are in need of repair, yet find themselves threatened

by scarcities of the resources that sustain their way of life. Or when,

in the face of these challenges, they turn for leadership to men in high

places—only to find those men as frail as any others.

So

sometimes the traveler is asked whence will come their succor. What is

to preserve their abundance, or even their civility? How can they pass

on to their children a nation as strong and free as the one they

inherited from their forefathers? How is their country to endure these

cruel storms that beset it from without and from within?

Of

course the stranger cannot quiet their spirits. For it is true that

everywhere men turn their eyes today much of the world has a truly wild

and savage hue. No man, if he be truthful, can say that the specter of

war is banished. Nor can he say that when men or communities are put

upon their own resources they are sure of solace; nor be sure that men

of diverse kinds and diverse views can live peaceably together in a time

of troubles.

But we can all remind

ourselves that the richness of this country was not born in the

resources of the earth, though they be plentiful, but in the men that

took its measure. For that reminder is everywhere—in the cities, towns,

farms, roads, factories, homes, hospitals, schools that spread

everywhere over that wilderness.

We can

remind ourselves that for all our social discord we yet remain the

longest enduring society of free men governing themselves without

benefit of kings or dictators. Being so, we are the marvel and the

mystery of the world, for that enduring liberty is no less a blessing

than the abundance of the earth.

And we

might remind ourselves also, that if those men setting out from

Delftshaven had been daunted by the troubles they saw around them, then

we could not this autumn be thankful for a fair land.

The 19th-century editor who pestered five presidents to make it a national holiday.

By Rich Lowry

It was 150 years ago that Sarah Josepha Hale gave us Thanksgiving as we know it.

The influential editor was the best friend Thanksgiving ever had. We are accustomed, in a more jaded and secular age, to wars on various holidays; Hale waged a war for

Thanksgiving. For years, she evangelized for nationalizing the holiday

by designating the last Thursday of November for it to be celebrated

annually across the country.

Besides plugging for Thanksgiving in her publication, Godey’s Lady’s Book,

she wrote Presidents Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan about it

before hitting pay dirt with Abraham Lincoln. On October 3, 1863,

Lincoln urged his fellow citizens to observe the last Thursday of

November “as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father

who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Hale had succeeded in her long-sought goal, but kept — as Peggy Baker notes in an essay

about her as “the Godmother of Thanksgiving” — writing editorials about

Thanksgiving for another dozen years. You might say that she was a bore

and nag on the topic, if her cause hadn’t been so splendid and her

understanding of Thanksgiving so clear-eyed, clairvoyant even.

Hale

saw the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving as the twin festivals of the

American people, “each connected with their history, and therefore of

great importance in giving power and distinctness to their nationality,”

as she put it in an 1852 editorial.

July Fourth celebrated

national independence and liberty, while Thanksgiving acknowledged God

“as the dispenser of blessings.” She argued that “these two festivals

should be joyfully and universally observed throughout our whole

country, and thus incorporated in our habits of thought as inseparable

from American life.”

Of course, Thanksgiving had existed on these

shores long before Hale took it up as a cause. Her description of a New

England Thanksgiving feast in her 1827 novel Northwood would

have been recognized by Norman Rockwell, and could apply with equal

accuracy to the average American home today. She described the table

“now intended for the whole household, every child having a seat on this

occasion; and the more the better.”

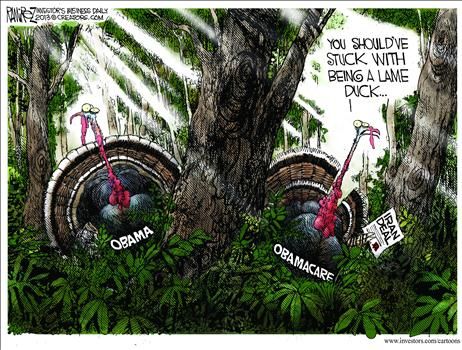

“The roasted turkey took

precedence,” she wrote, “being placed at the head of the table; and well

did it become its lordly station, sending forth the rich odor of its

savory stuffing, and finely covered with the froth of the basting.”

The

dessert course is almost as recognizable: “There was a huge plum

pudding, custards and pies of every name and description ever known in

Yankee land; yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche.”

Thanksgiving

had always been held in autumn, Hale explains in the book, “the time

when the overflowing garners of America call for this expression of

joyful gratitude.” But different states held it on different days, and

the holiday tradition was strongest in New England. Hale wanted to

guarantee Thanksgiving’s place in America’s firmament by making it a

national day.

She quoted the 19th-century British writer Robert

Southey in making her case. “Festivals, when duly observed, attach men

to the civil and religious institutions of their country,” he wrote.

“Who is there who does not recollect their effect upon himself in early

life?”

Hale understood the particular pull of Thanksgiving. She

wrote in 1837, “It is a festival which will never become obsolete, for

it cherishes the best affections of the heart — the social and domestic

ties.” (Although her faith in family bonds, re-fortified around the

Thanksgiving table, might have been a touch naïve: “How can we hate our

Mississippi brother-in-law? And who is a better fellow than our wife’s

uncle from St. Louis?”)

In her 1852 editorial, she predicted that

“wherever an American is found, the last Thursday would be the

Thanksgiving Day. Families may be separated so widely that personal

reunion would be impossible; still this festival, like the Fourth of

July, will bring every American heart into harmony with his home and his

country.” And so it does, still.